The Wages of War : The Cost of Freedom

Or the Inelasticity of Black Liberty

The Lion of Anacostia and the Black Quest for Liberty

Many, including my family, celebrated July 4th this past week in the United States.

I admit that more than the blessings of liberty, the holiday has always represented the familiar to me: family cookouts, fireworks, laughter, dancing, and music—a beautiful display of the mosaic of kinship.

In it, I find little reflection on the meaning of early American Revolutionary liberty from King George. I deeply resonate with Dr. W.E.B. DuBois’s reflection on the double consciousness of Blackness in the United States. For that reason, Juneteenth, the celebration of Jubilee, seems a more apt recognition of freedom—liberty when the least of us has it.

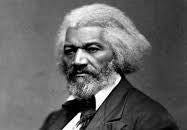

Liberty through the context of the most photographed man of the 19th century, the Lion of Anacostia, Frederick Douglass.

Photo credit: National Archives and Records Administration

Every 4th of July, without fail, for as long as I had sense enough to look it up, I revisit excerpts of Frederick Douglass’s “The Meaning of July Fourth to the Slave.”

Douglass, once called The Lion of Anacostia,1 begins his July 5th Independence Day celebration speech by commemorating the greatness of the American Founders (which reminds me of a College Debate Team tactic),

“Fellow Citizens, I am not wanting in respect for the fathers of this republic.”

Then he acknowledges that as a former slave, he, among all men, should be most critical, but that he recognizes that the ethos, dynamic, and principles from which the country’s foundational principles are built, at that point in history, were truly incomparable.

The point from which I am compelled to view them is not, certainly, the most favorable; and yet I cannot contemplate their great deeds with less than admiration. They were statesmen, patriots and heroes, and for the good they did, and the principles they contended for, I will unite with you to honor their memory.

Before he hits them with the question that frames the basis of the inquiry of this speech.

Fellow-citizens, pardon me, allow me to ask, why am I called upon to speak here to-day? What have I, or those I represent, to do with your national independence? Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us? and am I, therefore, called upon to bring our humble offering to the national altar, and to confess the benefits and express devout gratitude for the blessings resulting from your independence to us?

And the most recognizable question, the questioning of the irony of a celebration of liberty, with the grand elephant of slavery taking up space beyond the 36th parallel2 serves as the basis of the tension that exists between the celebration of independence and revolution, juxtaposed against the degradation of bondage, brutalization, and centuries of enslavement.

What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer; a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sound of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciation of tyrants brass fronted impudence; your shout of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanks-givings, with all your religious parade and solemnity, are to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy -- a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages. There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices more shocking and bloody than are the people of the United States, at this very hour.

It is this indictment that reminds me that even in the most well-resourced, most powerful nation in the world, where people come from all over to begin life anew and explore the promise that lies therein, race, particularly the categorization that gives rise to anti-Blackness, is the great blinding beacon that even outshines the promises of a gift statute’s liberty and progress.

As a practicing attorney, and in a deeper sense a legal scholar3 I can thank years of training and granular searches in meaning and how to construe for my deep questioning and reckoning with what this word actually means—liberty, or its oft-used sibling, freedom. I use them interchangeably.

What does it look like?

It certainly looks like something different for me than it did for the Honorable Frederick Douglass or my ancestors. In a sense, freedom is a specific thing and a spectrum.

It can be a moving target as you age.

It can be tied to notions of happiness that you outgrow. If you are imprisoned, it is likely similar in mechanics, if not in substance, to what it meant over 171 years ago when Frederick Douglass gave his speech.

Twenty years ago, it meant something different, even to me.

Freedom and how we define it is often tied to our level of happiness. Many of us measure our life’s goals and contentment by the degree to which we have the freedom we desire.

And as a shifting, growing, changing thing, freedom is very personal.

It is a good reminder, though, especially today when representation is not seen as good for its own sake but as a conduit to increase the awareness of a select few, and that even that notion deserves no protection.

Not so many moons ago, freedom was simply a notion, a question, a politically-willless desire for many millions.

And for the generational, specific, targeted discrimination that continues for their progeny, varying degrees of freedom will always be contingent upon how institutions, state, local and federal governments, and private companies disseminate opportunities, access, and equity that become the blessings of liberty.

Struggle bore freedom.

Struggle was war.

Struggle was boycotts of Jim Crow.

Struggle was a movement for civil rights.

Struggle was concentrated legal campaigns to highlight the disconnect between law and practice and constitutional rights.

Struggle was very literally fighting back.

Struggle was also non-violence.

Struggle was caring for, supporting, and uplifting your neighbor.

Struggle was a search for dignity and humanity.

Struggle, its memory, and its consistency all served the people's power to persist, break down the doors of obstacles, and allow freedom to burst forth.

If there is no struggle, there is no progress - Frederick Douglass

A Memory

“They were enslavers, not my family. I don’t need a crest—we make the name mean something!”

I was a high school senior during the fall of 2001 when the NCAA boycotted the state of South Carolina because of the Confederate flag controversy.

The NCAA ban of South Carolina in 2001 followed the NAACP’s ban of 1999 and the pressure of Black leaders everywhere to make the state change its position.

In 2000, the South Carolina state legislature “compromised.”

They removed the Confederate flag from the statehouse dome

(where it flew proudly at the very top)

→ to the statehouse grounds,

where it still flew very prominently beside a Confederate monument.4

During this same semester, in this especially racially-charged environment,4, my German-American English instructor insisted that we complete a family crest history project after reading Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet and Hamlet.

The irony was not lost on 17-year-old me that this was a fruitless exercise for a class of majority Black students—presenting European family crests to one another. I liked the idea of family and history, but the execution left much to be desired.

There were only three non-Black students, one of them Hispanic and the other two white.

The Hispanic student was exempted from showing a family crest because of his surname; he could talk about his family and their lineage.

I requested the same consideration, and the teacher laughed and said my surname has a family crest.

I was livid.

I insisted, mad at the teacher, of course, but also at my friends for not resisting—a moral slight and a personal one.

The Greene crest represented a British family that had roots on a colonial island I’d never visited, that sent traders to rob my ancestors from the coast of West Africa, to work the territory they had raided and invaded after their claim of “New World” discovery.

In this saga, my family was in bondage for centuries in the South Carolina Lowcountry.

And I was supposed to honor the people responsible for that particular cruelty—that very same family by presenting and discussing their crest with my classmates.

Blech.

Ick.

Yuck.

0 Stars—do not recommend.

Talk about cultural insensitivity and willful ignorance!

If there were ever a time for racial sensitivity training, back in 2001, this lady needed it.

Now to give some context, I’ve always had a smart mouth.

Always.

And usually, it got the better of me. But this time, using my voice seemed like one of the most justifiable occasions.

That’s what I thought.

The argument between myself and the teacher almost landed me in out-of-school suspension for refusing to complete an assignment and, in her words, for “trying to start a riot.”

Hyperbole much?

A riot?

Pfft!

Girl, please.

You’ve never seen a baker’s dozen Southern Black high schoolers so readily present European crests to a smiling white lady and indifferent class members.

Crazy, huh?

But more context—September 11th had happened about a month ago. The world was spinning. People were awash in the spirit of forced unity during hard times.

Looking back on it now, I get my friends, even my non-Black friends telling me,

“Look, you’re right.

It’s wild.

But is that the hill you wanna die on?”

“All of this crazy stuff is happening in the world. Let’s not have so much division. WWJD?”

“Dekera, the lady just giving the instructions now, how you gone tell her you’ne ga do it and you’ne even let her finish.”

“Senior year is supposed to be fun.

We’re just getting started.

Don’t let your mouth or this lady ruin it.”

“You know your mama gone trip if you get suspended. Shut up and sit your ass down. Let her have it.”

A big part of me got this.

I’m not a psycho after all; if everyone is telling you you’re mistaken or you shouldn’t do something, especially people you love, you listen.

But another part of me, the one that listened to my grandmother’s stories of her grandparents, who read the family reunion book of Sister Florence’s5 memory and wisdom passed down to all of us Greene descendants, was boiling mad.

When I thought about WIllis and Susie/Mama and Papa, the first free generation in my family, I couldn’t just let her have it.

Mama Susie raked hay piles for 2 cents as a girl.

She worked the farm and cared for her children alone when her husband was away working.

She buried seven of the 14 children she bore.

Let her have it?

Papa Willis left his family to work on railroads and saw pulpwood in the late 19th and early 20th century mills.

He would hand-carve toys for the boys and fill dolls with sawdust for his girls—loving reminders of him when he had to leave.

He worked twenty years to get back what was once theirs.

Nawl, eff all that.

The ancestors might be happy.

That I received an education,

That I became an advocate,

that I can even sound like a Comeyah at the drop of a hat instead of a Binyah,6

but they would be grievously disturbed if I engaged in their erasure.

“I’m not doing it. I refuse.”

“If you are silent about your pain, they’ll kill you and say you enjoyed it.” - Zora Neale Hurston.

Culturally-Clueless Teacher-Lady7 reported me to the principal, a Black man. At the time, I didn’t understand why he didn’t support me but instead called my mother to prevent suspending me as the teacher insisted.

A suspension would’ve resulted in me losing my top 5 class ranking. I was competing for valedictorian. Another student and I went back and forth each grade, from freshman to the beginning of senior year.

She and I were always #1 and #2, shifting spots each year. And I was the only Black person ranked in the top 5 of my graduating class at the start of my senior year. So this principal had more wisdom than I thought he did.

The compromise was for me to do two reports: on the crest of the family who enslaved my family and my family history.

I wrote a paper and gave a presentation on Willis and Susie. Papa scrimped, saved, and worked away from the farm part of the year, while Mama worked the land as hard as any man, raised half of her ch’ren8, and buried the other half.

Family history says that due to unjust white manipulation, a white man swindled the 100 acres that Papa managed to buy away from him.

In 1900, Papa and Mama married and were able to stay with Ma Tina (Mama’s mother who was formerly enslaved) for over eight years, working and saving to buy 100 acres.

They named it Greentown.

Everyone knew that that area of land off Highway 45 was Greentown.

Then, the white man, as he often did at that time, swindled.

Papa and Mama moved back with their children on Highway 45, then to Arthur Irving’s place, before moving back to Ma Tina’s since she’d recently married and moved on to her husband’s land.

Over the next two decades, Papa had to buy back 25 acres of the original 100 he rightfully purchased for his family.

Eighteen of those acres were bought over two decades, and the last seven were bought with money one of their seven adult children, Uncle Addison, sent back while serving abroad during World War II.

I was able to tell the story of Papa and Mama, Greentown, and even some about Ma (pronounced Maa like a sheep’s baa), Tina, and Mother Daphne (Papa’s mother).

I, unfortunately, had to do two projects.

I spoke of pride, blood, burials, crest colors, and wreaths.

I got my meaning; she got her decidedly empty exercise.

I still balk at having to do double work. Still, I’m glad that that white lady had to listen to the trial of my Gullah-Geechee family, knowing that I wouldn’t be suspended, wouldn’t lose my rank, and that she had been exposed for trivializing meaning, race, and history in a classroom, inside a state that relitigated (daily) a war fought over a century ago.

History matters here.

And not just the history and heritage of the people who worship a flag that dehumanizes their darker-hued neighbors and fosters detachment in their relations with them, but the history of the neighbors who are expected to swallow, in good humor, the onerous parading of the souvenirs of slavery—that which gutturally, viscerally, compulsively, objectively offends—that which fires up anger and bile in the bones and belly.

“Do not open your lips; die silent, as you shall see me do.” - Peter Poyas

You can choose to have dignity, even when you lack agency.

Especially when you don’t have freedom.

Sankofa.8

A wisdom gift from my ancestors.

—

Knowing history impacts the esteem of young Black children.

We create our futures based on the confidences of our past. It is a natural human inclination that is no exception to a particular race or group.

If your grandfather was a robber-Barron, monopolist, or President, your exposure and aspirations might reveal exponential opportunity—whatever future you’d decide to build for yourself. The industry might not matter.

You would know that those before you were great, so it is in you to be great. Their greatness, their progress, is almost evidence of your potential.

I am a testament to this.

I stood on my personal family history, so someone in an authoritative position couldn’t tell me about designing my “family’s” crest.

The cost of this knowing was great—generations paid it; the price tag, though, read free.

I fought to be heard because every Greene child in my family knows the sacrifices our forbears made. As a child who sat at my grandmother’s knee, who feasted on her family stories and times of old, I knew the kind of hard-working cloth I was cut from.

I knew that Papa couldn’t read, but people all over the county came to him for record-keeping of births, deaths, marriages, land purchases, etc.

So if my great-great-grandfather—functionally and mostly illiterate—served as a county archivist for Black folks at the dawn of the 20th century in Berkeley County, the largest county in South Carolina (regarding land area).

It is not a stretch that I would become a lawyer four generations later, with the benefit of the time I grew up in and the wonderful nourishment of my family.

It is no question that if Mama sewed quilts and the outside of dolls that Papa filled with sawdust, their daughter, my great-grandmother, would quilt, my Grandma and mother would sew clothes, and my brother would learn to do the same.

We are a reflection of those before us.

And even in the hard times and the difficult circumstances that one encounters, it is always safe to remedy yourself with the blood memory of who you are and where you came from.

Our children must know that we are brilliant, as much as they know the collective pain we endured. That they come from intelligent, imaginative, creative, resilient people.

There is freedom in this.

It is priceless.

This is a wonderful short article (around 300 words) on why Frederick Douglass was called The Lion of Anacostia. Anacostia is a neighborhood in Southeast DC.

The Missouri Compromise provided that Missouri could join the Union in 1820 as a slave state and Maine would join as a free state. The 36th parallel 36°30′ was the latitude and northern limit at which slavery was legal. The Compromise dictated that slavery was prohibited in the remaining states in the Louisiana Purchase north of that boundary, which was the southern border of Missouri. This is a good resource/short description and helpful overview map.

I wrote a law brief 15 years ago on using constitutional or international law and international covenants as a foundation for reparations for the descendants of enslaved Africans in this country. You can find it here.

What’s crazy about this is that they flew The Flag on the tippt-top of the dome. It flew higher than the Palmetto flag (our state flag). It flew higher than the American flag, which felt like a treasonous reminder of where you were. Don’t forget that South Carolina was the first state to secede from the Union, and the Civil War began with the firing on Fort Sumter in Charleston, SC, my birthplace.

Sister Florence, or Aunt Florence, was my grandmother’s aunt, one of the seven children of Willis and Susie who survived into adulthood. They had fourteen total, including my great-grandmother Beulah.

In the Lowcountry, a comeyuh is someone not from the Lowcountry, versus a Binyah, born and bred in the Lowcountry—coming here versus being/been here.

This behavior today would likely be classified as Karen-esque.

Sankofa is understood to mean “Go back and get it.” You can find out more about the term Sankofa here. I also used to visit this bookstore a lot back in the day. I used to attend a Pan-African book club on Fridays. Sankofa (the bookstore) is the epitome of Sankofa.

Dekera, this is one of the best things I've read all year. Period.

I love how you started with the historical context, and Mr. Douglass' powerful words. Magnanimous and cutting.

Your story is triumphant. The request was outrageous. The lack of compassion from someone who was a teacher is stunning. But this shows very well who you are and what you were willing to stand for. I admire your courage and I'm so happy you told this story. It will stick with me for a long time. Bravo!

This line at the end was beautiful:

"Our children must know that we are brilliant, as much as they know the collective pain we endured. That they come from intelligent, imaginative, creative, resilient people."

I have goose bumps.

Goose bumps at your courage, your history, your strong knowing, your representation of your family.

This is SO beautifully written, Dekera. A testament to all the generations of your family and their way with oral and written word, and to the many ghat will be inspired forward by it.

Freedom is relative.

I had saved this on the July 4 weekend to "read later". I'm grateful to @camilo for putting it in his Curated edition.